A conventional GPS (Global Positioning System) or GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) receiver has an accuracy that is at best 1 or 2 metres (3 or 6 feet), which is insufficient for some applications, most notably land surveys, and self-driving agricultural vehicles.

There are a few techniques that can be used to improve that accuracy, the most recent being RTK (Real Time Kinematics), which can produce centimetre-level accuracy (better than 1/2 inch). This is achieved using a receiver that can perform very detailed measurement of the satellite signal, combined with a stream of ‘correction data’ in RTCM (Radio Technical Commission for Maritime Services) format, that has been created by a nearby ‘base station’ performing continual measurements of the GNSS signal.

If you think that sounds complicated and expensive, then you’re not entirely wrong; whilst I can provide Python software that handles a lot of the complication, there is no denying that the hardware is quite expensive at present (hundreds of dollars), though there are some new devices coming on the market that could improve that situation.

GPS or GNSS

Before launching into the details, it is important to explain the difference between GPS and GNSS.

GPS is the original US group (‘constellation’) of positioning satellites, that has now been joined by systems from other countries (GLONASS, Galileo, BeiDu, NAVIC, SBAS and QZSS). The generic term for all these positioning systems is ‘GNSS’, but this term is not well known by the non-technical public, who may use the term ‘GPS’ to refer to all satellite positioning systems.

Over the years the original GPS system has evolved to cover more then one frequency band; the original L1 band at 1575 MHz has been joined by L2 at 1227.6 MHz and L5 at 1776.45 MHz. The newer bands can potentially offer better rejection of interference and handling of multipath signals, but at the time of writing, most GNSS receivers are single-band (L1 only).

Correction data

It is important that the correction data is obtained from a Base Station near the Rover; the further away the Base Station is, the worse the positioning. A theoretical figure for the accuracy is 8mm + 0.5ppm horizontal, so if the Base Station is 20 km (12.4 miles) away, the accuracy could be 18 mm (0.7 inches).

There are various ways to obtain the correction data:

- Local Base Station. A Base Station can be set up nearby, with a wireless link to the Rover.

- Commercial NTRIP service provider. There are commercial organisations that use NTRIP (Networked Transport of RTCM via Internet Protocol) to deliver the correction data. This can take the form of a Virtual Reference Station (VRS) that customises the data for the Rover’s location.

- Free NTRIP service provider. Some free NTRIP data sources are available, but the quality and reliability may not be as good as the commercial providers.

To keep the costs and complexity low, I’m using the last of these options, specifically the RTK2GO ‘caster’. This server continually takes correction signals from over 700 Base Stations world-wide; the ‘rover’ (RTK client) opens a TCP connection to the server, and requests a copy of the data from a specific Base Station. The client will then receive a continuous data stream over TCP, in the RTCM format that can be fed directly into a suitably-equipped GNSS receiver.

The advantage of this arrangement is a single Base Station can feed data to a large number of Rovers, without having to carry the burden of a lot of TCP connections; the server ‘casts’ one incoming data stream to multiple clients, and handles all the associated complexity, such as authenticating the user.

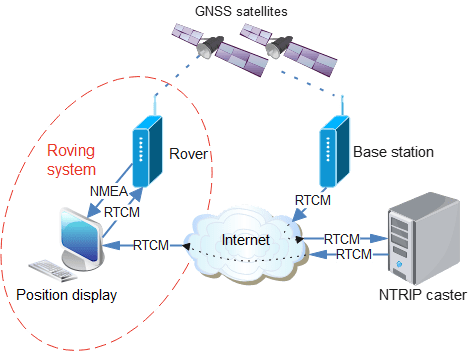

The diagram at the top of this post shows how the data flows from a Base Station to the NTRIP caster, then on to the display PC, which copies it to the GNSS receiver, which has an NMEA (National Marine Electronics Association) data output with (hopefully very accurate) position information. This must be a continuous process; if the supply of correction data stops, the GNSS receiver will drop out of RTK mode, and fall back to conventional lower-accuracy positioning.

Hardware

There are relatively few RTK-enabled GNSS receivers that can directly accept the RTCM correction data; for starters I’m using the ‘Ardusimple RTK portable Bluetooth kit’ which has the uBlox ZED-F9P receiver.

It has USB and Bluetooth interfaces that emulate a serial link, so the device appears as a COM port on a PC, and immediately starts outputting NMEA data at 115 kbaud as soon as it is powered up.

My uBlox receiver was supplied with v1.0 software, which needs to be updated using the u-center utility. If you do this without restoring the old configuration, then the receiver reverts back to 38400 baud operation; to restore this, select Configuration View, PRT (Ports) and set UART1 & UART2 to 115200 baud with NMEA enabled. One other essential configuration is to select NMEA, and tick the High Precision Mode box, to increase the number of decimal places in the position data.

When you click the ‘send’ button in the Configuration View, the settings are temporarily applied, so you can check they are correct. When the configuration view is closed, there is a prompt to save the settings to Flash, so they are non-volatile.

NMEA

NMEA (National Marine Electronics Association) have specified a standard for serial communication with GNSS devices. It takes the form of ‘sentences’, which are CRLF-terminated lines of ASCII data. The message starts with a dollar sign, the letters GP or GN, and three more letters specifying the type of sentence, then the data in comma-delimited format.

There are minor differences between different manufacturers’ implementations, so I’ve referred to the ‘u-blox F9 HPG 1.50 interface description’. It gives an example of the GGA sentence containing global positioning fix data:

$GPGGA,092725.00,4717.11399,N,00833.91590,E,1,08,1.01,499.6,M,48.0,M,,*5B

The first 2 letters are the ‘talker ID’ indicating which GNSS constellation has been used, the most common are ‘GP’ indicating GPS, and ‘GN’ for any combination of satellites.

092725.00 UTC time

4717.11399 Latitude in degrees and minutes ddmm.mmmmm

N North/south indicator

00833.91590 Longitude in degrees and minutes dddmm.mmmmm

E East/west indicator

1 Quality 0 = No fix, 1 = GNSS fix, 4 = RTK fix, 5 = RTK float

08 Number of satellites

1.01 Horizontal accuracy (Dilution of Precision)

499.6 Altitude above mean sea level

M Altitude units (metres)

48.0 Geoid separation

M Geoid separation units

*5B Checksum

The checksum is a hex value representing the exclusive-or of all the characters after the ‘$’ start, up to the checksum itself; e.g. in Python:

csum = reduce(lambda x,y: x^y, [ord(c) for c in line[1:-3]], 0)

if csum != int(line[-2:], 16):

print("Checksum error")

A common source of confusion is that the latitude and longitude are in degrees and minutes, not decimal degrees. To perform distance calculations, they need to be converted, and combined with a North/South/East/West indication as follows:

# Convert string with degrees & minutes to decimal degrees

def degmin_deg(dm, nsew):

deg = 0.0

if len(dm)>=4 and nsew in "NSEW":

n = 2 if nsew in "NS" else 3

deg = float(dm[:n]) + float(dm[n:]) / 60.0

deg = -deg if nsew=='S' or nsew=='W' else deg

return deg

The serial interface uses the ‘pyserial’ project, installed using:

pip install pyserial

This package provides functions to poll the serial interface, but to ensure no characters are missed, a separate thread is used, with a Python ‘queue’ to send the completed messages to the main program:

self.rxq = Queue.Queue()

# Start thread to receive serial data

def ser_start(self):

self.receiving = True

self.reader = threading.Thread(target=self.ser_in, daemon=True)

self.reader.start()

# Blocking function to receive serial data

def ser_in(self):

line = b""

while self.receiving:

if self.ser.inWaiting():

s = self.ser.read(self.ser.in_waiting)

line += s

n = line.find(ord('\n'))

if n >= 0:

self.rxq.put("".join(map(chr, line[:n+1])))

line = line[n+1:]

else:

time.sleep(0.001)

The serial read function returns binary data, which is converted to a string before being added to the queue. The normal approach would be to use the ‘decode’ function to convert binary values to a string, but it is quite common for a GNSS receiver to return pure binary data alongside the NMEA sentences, and this can cause a decoding error. So the ‘map’ function is used to convert each byte to a character, which is combined into a string using the ‘join’ function.

The remaining question is how to access the individual entries within the NMEA sentence; the obvious solution is to just to index into an array of values, e.g. for GGA:

data = line[:-3].split(',')

if data[0]=='$GPGGA' or data[0]=='$GNGGA':

fix = int(data[6])

sats = int(data[7])

To simplify the process of naming the data fields, I tried using a ‘named tuple’ e.g.

from collections import namedtuple

# Convert string to float, return default value if failed

def str2float(str, default):

try:

val = float(str)

except:

val = default

return val

# Define GGA sentence format

GGA = namedtuple('GGA', ['id', 'time','lat','NS','lon','EW','quality','numSV',

'HDOP','alt','altUnit','sep','sepUnit','diffAge','diffStation'])

gga = GGA._make(data[0:len(GGA._fields)])

fix = str2float(gga.quality, 0)

sats = str2float(gga.numSV, 0)

This technique works well provided the incoming data exactly matches the sentence definition; if there is one entry to many or too few, the process fails – and it is clear from the Interface Description that there are different message lengths depending on the firmware version. So I used an alternative dictionary-based technique, that is more tolerant of message differences:

GGA_S = ('id', 'time','lat','NS','lon','EW','quality','nsats',

'HDOP','alt','altUnit','sep','sepUnit','diffAge','diffStation')

GGA = {GGA_S[i]: i for i in range(len(GGA_S))}

# Get value from GPS sentence, given variable name

def getval(data, dict, s):

return data[dict[s]] if dict[s]<len(data) else None

quality = str2int(getval(data, GGA, "quality"), 0)

nsats = str2int(getval(data, GGA, "nsats"), 0)

NTRIP

The satellite correction data is in RTCM (Radio Technical Commission for Maritime Services) format, sent as a continuous stream over a TCP connection using NTRIP (Networked Transport of RTCM via Internet Protocol).

As indicated above, I use the RTK2GO caster to provide the correction data, but understandably they don’t like developers using experimental clients, since it can massively increase their server’s workload. So when testing the code, it is essential to use a local host. I use SNIP for this purpose (https://www.use-snip.com/download/) running on my Windows machine, so the host is “127.0.0.1”. It is possible to run SNIP without any license payments, the only issue is that it stops working after an hour, requiring a restart. This is only a minor inconvenience, and is quite reasonable, considering the amount of functionality that it provides for free.

When running production code, the host is set to “rtk2go.com”. You can obtain a ‘caster table’ listing all the available data streams by entering http://rtk2go.com:2101 in a browser; at the time of writing there are over 700 sources.

A data connection to the server is opened using conventional TCP socket calls:

host, port = "127.0.0.1", 2101

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

sock.connect((host, port))

Once a connection is established, the required data must be requested; this is similar to a Web page request, with authorisation in the form of name:password that is base64-encoded. See the RTK2GO Web site for details; basically the name is an email address, and the password is usually ‘none’ unless directed otherwise.

req = "GET /%s HTTP/1.0\r\n" % target

req += "Host: %s:%u\r\n" % (host, port)

req += "User-Agent: NTRIP %s/%s\r\n" % (CLIENT_NAME, CLIENT_VERSION)

req += "Accept: */*\r\nConnection: close\r\n"

req += "Authorization: Basic "

req += base64.b64encode(user.encode()).decode()

sock.send(req + "\r\n\r\n")

The ‘target’ is the name of the RTCM stream; if you are using a local SNIP caster, a suitable name is ‘Demo1’.

If the request is accepted, the server will respond with the brief text message “ICY”.

RTCM

The correction data is in RTCM (Radio Technical Commission for Maritime Services) format. This protocol is designed to keep messages as short as possible, to allow them to be sent over a low-bandwidth network. So the messages aren’t text-based, they are pure binary, and the data fields aren’t necessarily aligned on byte-boundaries.

A message starts with a marker of D3 hex, followed by a 16-bit length word (M.S.byte first) then a 24-bit ‘message type’ generally with a value between 1001 and 1304 that specifies the content of that message. For example, message 1006 gives the ‘station coordinates’, i.e. the location of the data source, in an x,y,z coordinate system, known as ECEF (Earth-centred, Earth-fixed).

The data source sends each message type at a controlled rate, the maximum being 1 per second, but it can be much lower. The caster specifies the rates for each message by giving the interval between messages, e.g.

1006(10), 1008(10), 1013(10), 1033(10), 1042(4), 1044(30), 1045(6), 1046(6), 1074(1), 1084(1), 1094(1), 1114(1), 1124(1)

This indicates that messages 1006, 1008, 1013, and 1033 will be sent every 10 seconds, but 1074, 1084, 1094, 1114, and 1124 will be every second.

At the end of the message there is a 24-bit CRC, and the total length of each message is a maximum of 1024 bytes. Unlike some other binary serialisation protocols (such as SLIP or PPP) there is no escape code when the start marker occurs in the body of the message, so it is quite possible the message data may contain one or more D3 values. This makes the start-of-message detection somewhat complicated, since it is necessary to check the length value and the CRC to decide if the D3 is a message starter or a data byte. Additionally, each block of TCP data may contain one or more messages, or perhaps just part of a message, or just a text string, which adds to the complexity:

# Get index of byte in data, negative if not found

def bin_index(data, b):

try:

idx = data.index(b)

except:

idx = -1

return(idx)

# Get next message from data

# If first char is not RTCM_START, then message is a text string

def get_msg(self):

d = b""

idx = bin_index(self.data, RTCM_START) # Get start of RTCM block

if idx>3 and self.data[idx-2]==0xd and self.data[idx-1]==0xa:

d = self.data[0:idx] # If text before RTCM..

self.data = self.data[idx:] # ..return text

elif idx == 0 and len(self.data) > 2: # Get length word

n = (self.data[1] << 8) + self.data[2]

if n > 1024: # ..check if valid

d = self.data = b"" # Scrub data if invalid

elif len(self.data) >= n + 6: # If sufficient data received..

d = self.data[0:n+6] # ..get data

crc = crc24(d) # ..check CRC

if crc == 0: # If OK, remove data from store

self.data = self.data[len(d):]

else:

print("CRC error")

d = self.data = b""

elif idx > 0:

print("Extra data")

self.data = self.data[idx:]

return d

It can be worthwhile decoding the Station Coordinates (message 1005 or 1006) to establish exactly where the station is, as the Caster Table only gives the latitude and longitude to 2 decimal places. However, you can just pass the messages straight through to an RTCM-compatible GNSS receiver, without having to perform any decoding, but it is advisable to validate (CRC check) each one, to filter out unwanted SNIP text.

Sending position to Caster

The system I’ve described so far uses a unidirectional link between the Rover and the Caster; having requested the correction data, the Rover receives a constant stream of data until the connection is terminated. However there are some circumstances whereby the Caster needs to know where the Rover is, in order to provide the correct data.

Commercial casters may provide a Virtual Reference Station (VRS) which customises the correction data depending on the precise location of the Rover; RTK2GO also provides a ‘virtual’ VRS service whereby the Caster will provide the nearest data source, so ‘NEAR-England’ should provide the nearest source in England.

For these services to work, the Rover needs to send its position to the caster. The format for this message is NMEA GGA, as described above. This should not be frequent, once every 30 or 60 seconds will suffice. It is important not to retransmit every GGA message, since this is usually once per second, which risks overloading the caster with unwanted data. If the caster doesn’t need the position information (because it isn’t providing a VRS), the data will just be ignored.

Demonstration software

The demonstration software is available on Github here. It is written in v3 Python, and can run under Windows or Linux. The only library used is pyserial, installed using:

pip install pyserial

The files are:

- gpsdecoder.py: serial interface to a GNSS receiver, and NMEA decode

- ntripdecoder.py: NTRIP and RTCM decode

- rtklient.py: console application

The console application has various command-line options, that are shown by running “python rtklient.py –help”:

usage: rtklient.py [-h] [--lat DEG] [--lon DEG] [--country STR] [-f] [-v] [-b NUM] [-c STR] [-m STR] [-p NUM] [-s URL] [-u STR]

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--lat DEG latitude (decimal degrees)

--lon DEG longitude (decimal degrees)

--country STR country name (3 letters)

-f, --find find nearest source

-v, --verbose verbose mode

-b NUM, --baud NUM GPS com port baud rate

-c STR, --com STR GPS com port name

-m STR, --mount STR NTRIP mount point (stream name)

-p NUM, --port NUM NTRIP server port number

-s URL, --server URL NTRIP server URL

-u STR, --user STR NTRIP user (name:password)

This is a command-line application, so runs under the Command Prompt in Windows, or a console in Linux. Prior to running it, plug in the GNSS receiver, and note which serial port this uses; on Linux, you can see this by running ‘dmesg’, and on Windows use the Device Manager.

Run the application in a console window that is at least 90 characters wide, specifying the com port, e.g.

python rtklient.py --port com3 # For Windows

python rtklient.py --port /dev/ttyUSB0 # For Linux

If Linux refuses permission to access the port as a non-root user, a quick Internet search will explain the possible methods to correct his. If the code does not run at all, check the Python version number using “python –version”; the code requires version 3.

The program first uses the data from the GNSS receiver to establish the current position; it waits until the 3-D fix is obtained, then shows the results, e.g.

Opening port com3 at 115200 baud

Waiting for GPS position (ctrl-C to exit)..

12:33:34 51.50735112,-0.12775834,32.013 GNSS fix

Contacting NTRIP server 'rtk2go.com'

752 source table entries

Mount point not set: use --mount

To obtain correction data from RTK2GO it is necessary to specify a user name and password; this can be entered using the –user option, or by modifying the DEFAULT_USER value at the top of rtklient.py. It should contain your email address, a colon, and a password. A valid email address is essential, but for most clients, RTK2GO doesn’t actually need a password, so a value ‘none’ can be used, e.g.

DEFAULT_USER = "me@mymail.com:none"

It is also necessary to choose a ‘mount point’, i.e. a source of correction data, amongst the 752 that are currently available. The command-line option “–find” can be used to check the distance to each mount point, and print out the five nearest, e.g. for Norwich UK:

python rtklient.py --com com3 --find

Opening port com3 at 115200 baud

Waiting for GPS position (ctrl-C to exit)..

12:33:34 52.63088612,1.29735534,32.013 GNSS fix

Contacting NTRIP server 'rtk2go.com'

752 source table entries

Finding nearest mount point

GBR HillFarm 14.4 km

GBR NR152QB 14.9 km

GBR IP23 39.6 km

GBR IP270RL 49.8 km

GBR JWBRTK 65.6 km

The “–mount” command-line option is used to specify the mount point, which is case-sensitive, e.g.

python rtklient.py --com com3 --mount HillFarm

Opening port com3 at 115200 baud

Waiting for GPS position (ctrl-C to exit)..

13:38:39 52.63088612,1.29735534,21.864 GNSS fix

Contacting NTRIP server 'rtk2go.com'

752 source table entries

Fetching RTCM data from HillFarm (ctrl-C to exit)

13:46:57 Pos 52.63088612,1.29735534,21.673 RTCM 1012 Dist 14253.215 RTK float

The last line is continually refreshed with a Carriage Return at the end; if the display scrolls continuously, the console window is too small, and needs to be expanded to at least 90 characters.

The RTCM value shows the latest correction message that has been received, and ‘RTK float’ indicates that the GNSS receiver is receiving the correction data, but hasn’t yet been able to get a full RTK fix; when that is achieved, ‘RTK fix’ is displayed, and the distance from the current location to the base station is shown, together with the maximum difference between the position values in metres. This gives you an idea of how much the position is changing over time, e.g.

12:20:59 Pos 52.63088612,1.29735534,21.673 RTCM 1127 Dist 14253.244 RTK fix Diff 0.030

This indicates that HillFarm is just over 14 km (nearly 9 miles) away, and with a static rover, the distance value has dithered by only 30 mm (1.2 inches).

If the receiver fails to get an RTK fix after several minutes, then the most probable cause is lack of signal from the receiving antenna; RTK does require a strong satellite signal, so it is important to have a good connection to a high-quality antenna, with a clear view of the sky.

Copyright (c) Jeremy P Bentham 2024. Please credit this blog if you use the information or software in it.