Mongoose TCP/IP is comprehensive easy-to-use TCP/IP software stack, produced by Cesanta Software Ltd.

In its simplest form, you just include 2 library files in your project, then can add a Web server using only 20 lines of source code, see the details here. The code is fully open-source, and the documentation is excellent; the only downside for some projects might be that a (low cost) license is required for commercial usage, but this is a reasonable request, given the amount of work that has gone into this high-quality package. Non-commercial projects can use the software for free, within the standard GPL licensing conditions.

The package supports the Pi Pico RP2040 CPU as standard, and there is an example program using the Wiznet W5500 Ethernet controller, the source code is available here. There is also an example of WiFi connectivity on the Pico-W, using the standard Raspberry Pi Application Programming Interface (API) but the result is quite complex, so I’ve replaced that API with my high-speed WiFi drivers, to produce a fast, flexible, and easy-to-use solution for TCP/IP on the Pico-W.

Mongoose

An unusual feature of the Mongoose TCP/IP software stack is that it isn’t tied to any operating system (OS); not only can run under Windows, Linux or a Real Time Operating System (RTOS), but it can also work completely standalone, with no OS at all. This is achieved by eliminating all the usual tasks, threads, semaphores, mutexes etc., and running everything within a main polling loop. This makes the code uniquely portable, and it works work well with my Picowi WiFi drivers, since they are also based on a polling methodology.

If there is no OS, how can Mongoose handle the request for Web server files, since the file-system doesn’t exist? The answer is that ‘static’ files (i.e. files that don’t change) can be embedded into the source code, and they will be returned as if they came from a conventional OS. Dynamic files can be returned by intercepting the file request, and creating a response on-the-fly.

In its simplest form, all the Mongoose source-code is in a single file, mongoose.c, with a single header file, mongoose.h, making integration into an existing code-base really easy; it is just necessary to call the polling function as often as possible, and handle the (optional) callbacks when a request is received by the Web server.

MG PicoWi

The starting-point for my project is the tutorial for Pico Ethernet using the W5500 chip, but there are some important differences between Ethernet and Wifi connectivity:

- Link failures. It is highly unusual for an Ethernet link to fail, since it uses a relatively secure plug-and-socket connection. Wireless links are much less secure, since they are competing for use of a shared medium (a specific radio channel) which can become very congested, leading to a high failure rate.

- Security. Since the communications medium is open to all, it is necessary to establish a secure link, as a precaution against eavesdroppers. There are various schemes in use; at the time of writing, the most common is Wi-Fi Protected Access 2 (WPA2), with WPA3 just starting to become available.

- Negotiation. As a result of the above, there is a significant amount of negotiation between the unit (known as a ‘station’ or STA) and a central hub (known as an Access Point or AP) when a unit wishes to join a WiFi network, and there is the distinct possibility of failure, e.g. if the STA has the wrong WPA encryption key. Compare this with Ethernet, where is it just a question as to whether the cable is plugged in to both units or not i.e. the network is ‘up’ or ‘down’.

The above points just refer to the establishment of a Wifi link between STA and AP, but there may be other negotiations as well, most notably obtaining an Internet Protocol (IP) address using Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP). So it is important to have a robust mechanism for handling low-level network faults, and a way of informing higher-level code that the low-level link is broken, so nothing can be sent or received. I’ve also indicated a visual indication of the connection status, flashing the on-board LED at a fast rate if disconnected, slowly if connected.

Initialising the WiFi interface

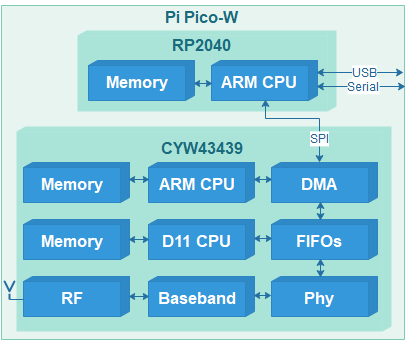

The WiFi chip on the Pi Pico W is the CYW43439, and it contains 2 CPUs, with the attendant memory and peripherals. As a result, initialising the chip is quite complex; for example, it is necessary to load 230 KB of firmware into its memory every time it is powered up. My Picowi project describes the chip initialisation in considerable detail; if you want to learn about the low-level hardware & software interfaces, see part 1 and part 2 of that project.

Once the firmware has been loaded, and the chip CPUs are running, then there are many more commands to configure the interface; these are also sent by the PicoWi software. In the event of an error, there isn’t any corrective action that can be taken, apart from power-cycling the chip, and repeating the whole initialisation process.

Joining a network

The software connects to a WiFi network, that is specified by:

- SSID. This is the Service Set Identifier, a string broadcast by the Access Point (AP) containing the network name. This is not to be confused with the Basic Service Set Identifier (BSSID); this is the low-level Media Access and Control (MAC) address of the AP, which is not needed.

- Encryption protocol. This specifies the method that will be used to secure the WiFi transmissions. If the network is ‘open’, then there is no security, and the transmissions can easily be monitored and intercepted. The early security protocols such as WEP (Wired Equivalent Privacy) provide minimal protection, so the more modern WPA (Wi-Fi Protected Access) is generally used, with its successors WPA2 and WPA3.

- Password. This is the secret encryption key used to encode & decode the transmissions; for WPA it is a string with a length from 8 to 64 characters.

It is not unusual for the network connection attempt to fail, so the code is contained within a loop, and a retry is performed after a suitable delay.

Transmission and reception.

The Mongoose stack is designed to handle a variety of network drivers, that are specified using a single structure with pointers to functions for initialisation, transmission, reception, and network state reporting:

struct mg_tcpip_driver {

bool (*init)(struct mg_tcpip_if *);

size_t (*tx)(const void *, size_t, struct mg_tcpip_if *);

size_t (*rx)(void *buf, size_t len, struct mg_tcpip_if *);

bool (*up)(struct mg_tcpip_if *);

};

This structure is populated with pointers to the corresponding PicoWi functions:

struct mg_tcpip_driver mg_tcpip_driver_wifi = {

mg_wifi_init,

mg_wifi_tx,

mg_wifi_rx,

mg_wifi_up };

The transmit & receive functions call the corresponding functions within PicoWi:

// Transmit WiFi data

static size_t mg_wifi_tx(const void *buf, size_t buflen, struct mg_tcpip_if *ifp)

{

size_t n = event_net_tx((void *)buf, buflen);

return n ? buflen : 0;

}

// Receive WiFi data

static size_t mg_wifi_rx(void *buf, size_t buflen, struct mg_tcpip_if *ifp)

{

int n = wifi_poll(buf, buflen);

return n;

}

It is important to realise that the polling of the WiFi chip isn’t just to receive data, it is also to receive other ‘events’, such as notifications of the network state. Furthermore, Mongoose does not call this function if the network is ‘down’, so there is a risk that the network will be permanently stuck in the ‘down’ state, since the WiFi chip isn’t being polled for events to show the network is ‘up’.

The solution to this problem is to include additional polling in the main loop:

if (!mif.driver->up(0))

wifi_poll(0, 0);

This polls the WiFi interface if it isn’t reported as ‘up’, so that the change-of-state can be detected. The zero parameters ensure that in the ‘down’ state, any incoming network data is discarded, since nothing useful can arrive until the the network has been joined.

Polling

To those unfamiliar with embedded systems, the extensive use of polling might seem to be counter-productive, resulting in a much slower response to network events – wouldn’t it be quicker to use interrupts?

The answer to this question comes from a deeper understanding of what actually happens within a multi-tasking system. To give an interrupt-driven system a quick response-time, it is important that the interrupt hander doesn’t do much; it has to rapidly save the incoming data, without doing much processing, in order to be ready for the next message. So it will set a semaphore, that will wake up another process that decodes the message format and prepares a response, which is put in a queue for transmission. Then another context-switch will pass control to a transmit routine, to send the response out. It is important to ensure that the hardware isn’t being accessed by 2 routines at the same time, so mutual exclusion (‘mutex’) flags have to be used to guarantee this.

This logic is quite complex, and due to its dynamic nature, is difficult to test & debug; an error can cause the network driver to stall, until an idle-timer expires, and triggers code that tries to resolve the situation.

For this reason, the overall simplicity of single-threaded polled code can appear quite attractive; interrupts can still be used for real-time processing (such as scanning a keypad) whilst the network code keeps running in the background.

Web server

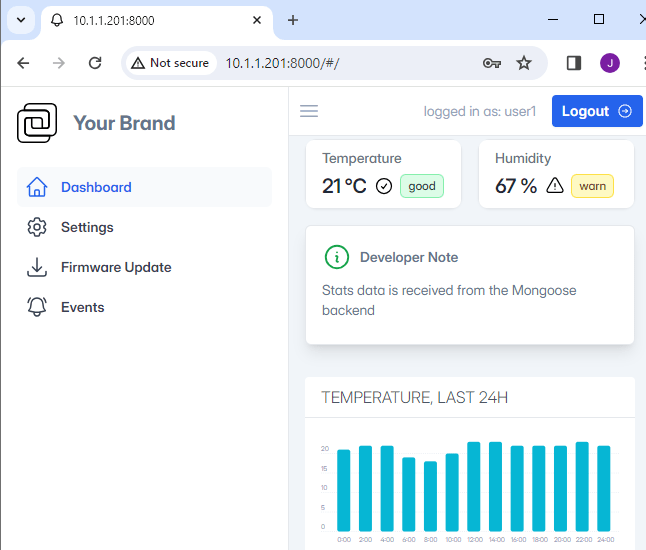

The Web server (web_server.c) is described in considerable detail in the Mongoose documentation, so there is little I can add. If you log in using one of the given identities, there is a demonstration of various features, but sadly the most interesting (such as Firmware Update) are just dummy functions; extra code is needed to make these operational.

Bulk data transfer

I have previously said that the Web server can provide static (read-only) files from its compiled-in filesystem, and small dynamic files by intercepting the file request callback, and generating the HTML code on-the fly. However there is another use-case; what happens if we want to return a very large file on-the-fly, for example, a picture from a Web camera? Cesanta have provided a ‘huge response’ example, but it involves chopping up the data into smaller sections, and reassembling them on the client using Javascript. I’d like to display the image by simply pointing the browser at its location, so this technique isn’t suitable.

There is an alternative method; just emulate a filesystem containing the file we want to send. When accessing the file, Mongoose starts by issuing a ‘stat’ call to get the data length & timestamp, then follows with an ‘open’ call, multiple ‘read’ calls, and a ‘close’ call. It is easy to intercept these file calls, since they are function pointers in a file API structure:

struct mg_fs {

int (*st)(const char *path, size_t *size, time_t *mtime); // stat file

void (*ls)(const char *path, void (*fn)(const char *, void *), void *);

void *(*op)(const char *path, int flags); // Open file

void (*cl)(void *fd); // Close file

size_t (*rd)(void *fd, void *buf, size_t len); // Read file

size_t (*wr)(void *fd, const void *buf, size_t len); // Write file

size_t (*sk)(void *fd, size_t offset); // Set file position

bool (*mv)(const char *from, const char *to); // Rename file

bool (*rm)(const char *path); // Delete file

bool (*mkd)(const char *path); // Create directory

};

Having created our own file handler functions, we can define a new virtual file interface, and specify that it should be used for a specific filename:

// Pointers to file functions

struct mg_fs mg_fs_live = {

p_stat, p_list, p_open, p_close, p_read,

p_write, p_seek, p_rename, p_remove, p_mkdir

};

// In the HTTP connection callback...

struct mg_http_message *hm = (struct mg_http_message *) ev_data;

if (mg_http_match_uri(hm, DATAFILE_NAME))

{

struct mg_http_serve_opts opts = { .fs = &mg_fs_live };

mg_http_serve_dir(c, hm, &opts);

}

Picomong

This is a port of the mongoose Web server and device dashboard onto the Pi PicoW, using the picowi WiFi driver in place of the conventional lwIP code.

The network details are hard-coded in the firmware, so the file ‘mg_wifi.c’ needs to be edited, to change the default network name (SSID) and password.

It may also be necessary to change the network security setting, the options are:

WHD_SECURITY_WPA_TKIP_PSK, WHD_SECURITY_WPA_AES_PSK,WHD_SECURITY_WPA_MIXED_PSK, WHD_SECURITY_WPA2_AES_PSK, WHD_SECURITY_WPA2_TKIP_PSK, WHD_SECURITY_WPA2_MIXED_PSK,WHD_SECURITY_WPA2_FBT_PSK, WHD_SECURITY_WPA2_WPA_AES_PSK, WHD_SECURITY_WPA2_WPA_MIXED_PSK,WHD_SECURITY_WPA3_AES, WHD_SECURITY_WPA3_WPA2_PSK |

I have had difficulties with the WPA2_WPA and WPA3_WPA2 settings, so have generally found it best to use PSK with WPA, WPA2 or WPA3.

There is a serial console, with transmit data on pin 1 of the PicoW module, at 115200 baud. When the unit powers up, the on-board LED will flash rapidly, and the console will display something similar to the following:

WiCap v0.26

Using dynamic IP (DHCP)

Detected WiFi chip

Loaded firmware addr 0x0000, len 228914 bytes

Loaded NVRAM addr 0x7FCFC len 768 bytes

MAC address 28:CD:C1:00:C7:D1

Joining network testnet

WiFi wl0: Nov 24 2022 23:10:29 version 7.95.59 (32b4da3 CY) FWID 01-f48003fb

Joined network

IP state: UP

IP state: REQ

IP state: READY, IP: 10.1.1.78, GW: 10.1.1.1

The dynamic IP address will depend on the settings of your network Access Point.

Once the unit has connected to the WiFi network, the LED will flash more slowly (1 Hz); it should respond to network pings, and the Web server will be available on the usual port 80.

The source code is on github here.

Copyright (c) Jeremy P Bentham 2024. Please credit this blog if you use the information or software in it.